|

“I’d shoot for the moon but I’m too busy gazing at stars." Not Afraid, Eminem

My first quarter of foraying into personal OKRs is complete. I absolutely loved having these OKRs and use my OKR document as the centralizing piece of my personal life. Without further adieu, a review of Q1 and a look forward to Q2. 2019 Q1 Objectives - Review

What stands out most in the past 3 months:

2019 Q2 OKRs

What I am most excited about in the next 3 months:

"I guess we'll never know what Harvard gets us,

but seeing my family have it all, took the place of that desire for diplomas on the wall" Drake, Crew Love When discussing my company with family or friends, the heuristic most people use to gauge company success is headcount. This same heuristic is often a talking point for CEOs/founders with media and often cited in articles. This is so fucking dumb and dangerous for businesses. Whenever I encounter someone who asks me about actual measures of a successful business - gross margins, unit economics, LTV, etc - my heart skips a beat. I wanted to document why I think aggressive fighting against growing headcount (even while scaling) is important. 2 quick notes: (1) my views are strong but weakly held, data to the contrary will always change my beliefs; and (2) aggressively fighting headcount still means you can hire, but makes it a conscious, difficult decision rather than the solution to all problems. Without further ado, why increasing headcounts in an organization sucks: Headcount disincentives ownership The larger the staff count, the harder it is to feel ownership. The ideal size of a department is 0 or 1. Once there are teams of team, the head of a department loses ownership because they are responsible for the output of teams but find it harder to feel like an owner. Feeling and acting like an owner is one of the single biggest predictors of success. What are the signs that someone is an owner? An owner picks up trash in the office, an owner spends company money like their own, and an owner feels deep personal responsibility for failure and success. The further you remove an owner from the impact of their ideas and the “doing of things”. John Boyd summed this concept up well by asking his mentees “Do you want to be someone, or do you want to do something?” Owners do something. Also, by giving people ownership you can hire and keep the right people. Great operators want to own things – if you give them full control of an issue they will usually feel empowered and enjoy their job. People will create work The pervasiveness of people creating work in modern companies is crazy. It is value destructive and any sign of it should be crushed immediately. Recently, I was at an airport in Geneva and there were 5 staff members who were organizing the line to security. I observed them pretty closely for 2-3 hours and nothing they did ever changed anything about the line or the efficiency of the system – but they looked busy and were constantly moving things and chatting with each other. The optimal solution was to just leave the line alone (the number of people needed to do the job was zero). They should all be fired immediately (I say fired rather than reassigned because a competent person wouldn't tolerate being in a fake work position). Just last week, in an exchange at work with a partner company, I was slapped in the face with screaming ineptitude and fake work (in fairness it was the partner's partner so probably exacerbated things). At this other company there is a team (not even a person) that must sign-off on partner marketing. This team is given a checklist of things to look out for and are essentially incentivized to do the following:

Why do they have those incentives? Because their job is to approve or disapprove things! By taking 5 business days and making a list of things that are wrong they are justifying their job. One of the 2 “errors” we made was having an object within half an inch of their logo on a landing page – I'm so glad we got that resolved! Now they can point to all the work they do and be vindicated by the organization's decision to have them on staff. A normal business – one where an owner made decisions - would make this 1% of 1 person’s job and make it clear – as long as it’s not wrong then its fine. Move forward and do something. As Charlie Munger has stated – “Well, I think I’ve been in the top 5% of my age cohort all my life in understanding the power of incentives, and all my life I’ve underestimated it.” Given the incentive is high – point out every single issue to keep your job – there will always be an issue with something we send over. As you hire more people, the likelihood that someone in your team or your company is adding zero value or decreasing value multiplies. Don’t risk it. Headcount means bureaucracy because people are nice Companies want people to feel valued and that they are making a difference (yay). Companies tend to do this in a few ham-fisted ways:

All this will change a fast moving company to a slow moving corporate blob in the blink of an eye. Good decisions aren’t made with 14 people in a room, democracy in decision making is dumb when everyone isn’t fully informed, and more teams create silos of information and people you need to “run things by.” This will crush even a 30-person company if you aren't vigilant. 50% of my job is just fighting these things from occurring, aggressively. Luckily, I hate these things with a passion so its going fine. Realize pain = fun in the long run This is probably the hardest one to grasp but the most important. When you keep headcount lower than a normal company by an order of magnitude (say 50 v 500, not 50 v 60), you will feel pain. This pain will mean that when someone is on vacation things don’t get done as well. It will mean when you have a customer facing emergency you will bemoan not having more people to help. It will mean you lack expertise in many areas. It will mean that things will suck, often. Looking back at events or even long periods (months) that really sucked at work – I often look back with happiness. It honed our operational excellence. It brought us closer as a team. Shared pain is the greatest builder of relationships. I look at where I've become closest with friends, it’s always through shared painful experiences (sports team, pledgeship in a fraternity, 100 hour work weeks as a lawyer). Recently, I went to a wedding that was a logistical nightmare. We couldn’t get on and then off an island where the wedding was taking place. People were stranded and 90% of the wedding missed their flights home. I’ve never had a more fun wedding – I made new friends and solidified bonds with old ones more than any enjoyable evening out. Those same principles apply in the work place. Sub 50 Word Summary Adding headcount must be deliberate and a measure of last resort. Adding people reduces ownership and increases the likelihood of mediocrity. Embrace understaffing. Embrace working harder. Fuck 12-persons meetings and running things by different groups. Do work. "I ain't in it for the fame, I ain't in it for the glory

I'm down to die for it, absolutely mandatory Respect this hustle, respect this hustle" - Respect this Hustle, TI New year, clean slate. While I generally despise weak platitudes about “this is the year I want to get in shape” for new years resolutions, I fucking love OKR (objectives and key results) at work so I wanted to roll them out in my personal life. To see all my objectives and key results – check out this sheet. I’ll be updating the sheet once every 2 weeks for anyone that wants to track my progress. If I fail in any objectives, then I will fail publicly. I’m not going to dive into the key results here but rather wanted to write out my objectives and insight as to why I choose them (for all of 2019 and then for 2019 Q1). If anyone else is doing personal OKRs, I'm looking for an accountability buddy so let me know (DM me on twitter @Dbrychcy). 2019 Objectives:

2019 Q1 Objectives:

Looking forward to writing a lot more in the next year and hopefully not fucking up all my objectives too bad. “Middle finger to my old life” Jay-Z, Who Gon Stop Me

As we close the chapter on 2018, I wanted to reflect on the year. I’m breaking this up into 3 parts – grades, worst of, and best of. In an exercise of brevity, I’m going to try to keep this in bullet point format as I tend to write 5,000 words when 50 will do (it's still long). Grades

Overall GPA of 3. I'll be posting later today or tomorrow my 2019 objectives, so hopefully this scoring will be more quantitative rather than qualitative next year. Worst of 2018 Before going into what was good, I want to embrace some of the suck in 2018.

Best of 2018 Now that that cathartic exercise is complete - on to the good about 2018. I've tried to keep the lists as short as I could.

"You need git up, git out and git something

How will you make it if you never even try? You need to git up, git out and git something Cause you and I got to do for you and I That's why" Outkast, Git up Git out I started my job as a lawyer on October 8th, 2012. My last day as a lawyer was October 8th, 2014. I survived 2 years, 0 months, 0 days. This is my story on why I decided to go to law school, my journey into Big Law, why being a lawyer is the worst, why people don’t quit sooner, and how I escaped into freedom. Hope you enjoy this mini-novella. Why I went to Law School 3 simple reasons: Money. Money. Money. My undergraduate degree at Georgia Tech was in Civil Engineering. I always knew, anecdotally, that engineering is a generally safe and well-paying job in the United States. The stats – graduating from Georgia Tech, the median salary for civil engineers is $60,000. The top-end civil engineers make $113,000 per year (with 10+ years of experience). That’s pretty solid. Unfortunately, during my 3rd year at Georgia Tech, I found out the lawyers were being offered $160,000 starting salary right after law school at top law firms (it was $130,000 for top firms in Atlanta and $160,000 for top firms in NYC). Essentially, I was being told I could become a successful civil engineer and make $113k or I could just graduate law school and make $130k with a $20k bonus. With that one nugget of information, I decided I wanted to be a lawyer (in fairness, I was torn between being a lawyer or a doctor and oscillated between the two for a couple months because doctors also make a lot of money). Was this a dumb reason to select a career path? Absolutely. Did I talk to any lawyers in my making my decision? Absolutely not. So I set off on my new life plan. That summer I studied for the LSAT (the law school entrance exam) and did alright. I applied to ~8 schools and ended up choosing the University of Georgia (UGA) because they offered me a full academic scholarship. It wasn’t the highest ranked school I was admitted into, but tuition at the other schools would be $45,000 per year. I chose “free” law school. Side bar: I was graduating from Georgia Tech in May 2009, which was one of the worst times to be hitting the job market as a new college graduate as almost no one was hiring. This was particularly acute for construction companies that were some of the hardest hit by the 2008 Great Recession. This was likely a big contributing factor to my thinking that 3 more years of school would be a good idea. Getting a Big Law Firm Job From the first day of law school, my only goal was to get a job at one of the big law firms in Atlanta. This is where things get interesting. The downside to having chosen to UGA, is that it wasn’t in the prestigious “T14” law schools. The T14 is a collection of the top 14 law school in the country (there are about 150 ranked schools). Going to a T14 school essentially increases your likelihood of getting a big firm job because those firms primarily hire from T14 schools. UGA was ranked number 30. To get a big firm job out of UGA, you essentially needed to be in the top 10-15% of the graduating class (it’s a bit more complicated and ridiculous but I’ll get into that in a second). The problem with finishing in the top 10% of this next tier of law schools (generally those ranked 15-50), is that 80% of students thinks they will be in the top 10%. This creates 1 spot for every 8 people that believe they will achieve that result. Add on to that, the fact that these are all people who are accustomed to succeeding. They have all done well in their undergraduate studies and done well on their LSAT. This creates a huge imbalance of perception to reality. Now, let’s continue down the rabbit hole of getting a big firm job and just how fucking ridiculous the system really is. In your first year at law school, known as 1L, everyone takes the same first year courses and you usually get grades for your first year at the very end of your first year (caveat: this is how most law schools are structured but there are differences). Essentially, your first semester is worth 33% of your final 1L grades and your second semester is worth 66%. Your 1L year matters more than most people understand. After 1L most people take unpaid internships or any legal job they can get for the summer. Most of these jobs aren’t based on your grades because you apply in January/February and you don’t have any real grades yet. However, you start interviewing for 2L summer job (the jobs you take after your 2nd year) in August and September (before you start your 2L year). Essentially, if you are trying to get a big firm job then the only data point is your first year of grades. I received an offer in September of my 2L year (10 months before I would start) for my 2L summer job. The 2L summer job is one of the greatest jobs of all time. You get paid $3,000 per week, the hours are easy, not much is expected out of you, and every week you are seduced with sporting events and open bars. It is amazing and has nothing in common with being a lawyer. After the summer is over, the law firm then decides if they want to make you an offer. So in August, before I even started my final year of school I landed a 6-figure job in Atlanta plus a signing bonus plus all my Bar training and exam expenses paid for in full. The major issue is that if you don’t get an offer after your 1L year for a 2L summer internship its almost impossible to get a big firm job. 95% of first year law firm associates spent the 2L summer at that law firm. So if you screw up your first year, its almost impossible to get a big firm job. Let’s recap how to ensure you get a 6-figure job right out of law school:

So 1 year of hard work and 2 years of making sure you don’t fuck up. Then you achieve the holy grail – a big law firm associate job. The Life of a Big Firm Associate (Why being a lawyer is the worst) From the outside, being a big law firm associate seems awesome. From the first day, you get our own office (inclusive of book case, L-desk, 25th floor views), amazing benefits, a secretary, and you are surrounded by extremely smart people. But then reality sets in. And reality is dark. Let’s jump in to all the terrible things about being a law firm associate (plus why being a partner isn’t much better):

Why People Stay Despite my grievances above, I want to examine why so many people remain at law firms. Here is my best distilled version:

Why and how I left I made it 160 days into my legal career before semi-publicly claiming I wanted to quit being a lawyer. 160 days. Scouring through old e-mails I found my first, “I hate being a lawyer and need to quit this job e-mail.” It was sent to one of my best friends and funniest people I know, Aidan Shaughnessy, on April 17th, 2013. I told her I wanted to buy a place in Montenegro and start a hostel. When she asked why I don’t just go for it. I replied succinctly and with poor grammar – “I need to work here for at least 2 years Eth! Gotta build that resume.” I fulfilled that promise and not a day more. So how did I get out? Giant leap of faith. After my first major trial ended in Denver in July of 2014, I was going to take 2 weeks off of work and go to Europe in August. This was my first real vacation since I joined the law firm. However, my vacation was more of a career transition trip. My goal was to check out some top-MBA schools in Europe and study for the GMAT that I was taking in September. My trip took me to Budapest (for fun), to Poland (to visit family), and then off to Paris (visits HEC and Insead) and then to London to check out London Business School. Prior to arriving in London, I e-mailed an old Georgia Tech friend, Alexis Luck, who lived in London to see if she wanted to grab beers. She agreed to meet on Saturday August 30th for beers at her local pub in Notting Hill. She also told me that her husband, Dave, would be joining (or as he puts it now “I was not excited to be wasting my Saturday with some random loser from Georgia Tech”). Once we sat down at the pub, we started discussing why I was in Europe, why I was leaving the law, and my plans to get an MBA. Dave told me about his start-up, Capital on Tap. He also said that he was always looking for smart people and that he thought MBAs were dumb. We continued to drink for many more hours and then parted ways as I had to drunkenly take a train back to Paris that night. A few days later, on September 3rd, I followed up with Alexis asking if I could have Dave’s e-mail. I sent him a short e-mail the next day: Hi Dave: I wanted to follow up with you about our conversation this past weekend. As you know I am quite disenchanted with my current job. I am very interested in being part of a rapidly growing organization and helping to continue the expansion. If you think there is a position for me at your company, I would be very interested to discuss further. I am very flexible as to my role, position, and my salary at Capital on Tap. I attached my CV if you were interested in taking a look. Look forward to hearing from you. That was it. Reeks a bit of desperation, but whatever. I would have joined as administrative assistant or a CFO, I didn’t give any fucks. I just wanted to get the hell out of law. It took us about a week to get a call setup but then things moved quickly from there. I accepted the position (no title – just “help me with important projects”) on Tuesday September 16th, sold my condo on Sunday October 5th, had my last day at my law firm on Wednesday October 8th, took a redeye to London on Thursday October 9th and had my first day at work on Monday the 13th. I doubt I will ever have a more life-changing month ever again, but it was fun. So what would I tell lawyers who want to leave the big law life:

A few nice words about my time as a lawyer I’d be remiss if I didn’t mention what I got out of my two years working at my law firm. First, the lawyers I worked with were exceptionally smart. I focused on construction litigation so most of the lawyers in my group had both engineering and law degrees. The intellectual horsepower at a good law firm is something that is hard to replicate almost anywhere else. Second, I learned what hard work was. People spend a lot of time talking about work-life balance these days. I think spending a year doing 80 hours+ a week every week is humbling and will teach you a lot about yourself. Combining smart people with strong work ethics is a recipe for success, I don’t care what about work/balance “expert” says. Third, one of the partners, Chad Theriot, essentially took me under his arm after about 6 months. Not only is he extremely smart and exceptionally kind but was the best teacher and motivator I could have ever asked for as a young lawyer. He was the only reason I made it 2 years and when we were travelling for work and working together, it was fun. Like not even kind of fun, but actual fun. He also shielded me away from having 6 bosses since he had enough work to keep my busy. Fourth, and this doesn’t fit perfectly in this category, but a thank you to my parents. To have supportive parents along each step of my life journey is such a blessing that I took for granted for many years. In college, I would call up my parents and tell them I wanted to go to law school, a month after telling them I wanted to be a doctor, and they would just tell me “ok sounds good.” When I called them and told them I’m quitting my legal job, a job that I had gone to school an extra 3 years for, and then add on top of that that I was taking a huge risk at a tiny start-up – they said it sounded a bit risky but it could be a lot of fun. Part of me wishes they would have told me “hey you are making a bad decision” or “maybe give it a month to make sure you want to do this” or even “have you talked to anyone who has joined a startup in London”. You know, the basic questions. But alas, I’ll settle for the most supportive parents imaginable. Also, I should mention I was a mediocre lawyer In case this ever reaches the eyes of my fellow lawyers, I want to make clear that I was a mediocre lawyer. I was only good at 1 thing – working a lot. I embraced 9/9/6 – 9 am to 9 pm, 6 days a week. I was a workhouse. Having said that, as someone who has a natural distaste for all authority and rules, I was difficult to manage and just did my own thing a lot. If I thought I had a better way than a partner/senior associate, I usually did it my way. I’m a terrible employee. "Man I murder for fun but my job is never done

From morning morn' to the setting of the sun" Gucci Mane, Murder for Fun This is my personal tirade against Slack - the business "productivity" tool I hate the most. If you also hate Slack, I hope you find reading this as cathartic as I found writing it. If you really like Slack, you are a lost cause. I'll add two caveats before I go on what I believe will be an expletive-riddled screed. First, my experience is based on using Slack in a relatively small company (60 people) and all of us in a single location. I can't imagine its usefulness for a largely distributed team, but I have been told it is good for that. Second, I love the Slack business model - selling into developers or smaller teams, simple and transparent pricing, very little integration upfront, and a very sticky proposition once companies get on Slack. These are all beautiful business concepts and Slack is one of the best SAAS businesses out there. Now that the niceties are out of the way, here are a few of the reasons why Slack is the fucking worst. 1. Most business conversations should be asynchronous. Slack tries to make it easy to connect in real-time with co-workers, creating a simple direct messaging and group messaging system to help businesses communicate. What actually happens is more akin to a water cannon filled with shit aimed at everyone in your business. A little history to start. When we first started using Slack 2 years ago, it started off relatively innocuously. A general channel for general company announcements (people going to the pub, the need for an iWatch charger) and some direct messages. I thought, "Hey this is great. Its like gchat with a better UX/UI and a great place to communicate quickly with the entire company. " I was a fan. Fast forward 6 months later, I'm a member of 20 different channels and 50 direct messages. The channels are where the greatest travesties are committed. For those of you that don't use Slack (you are so lucky) channels are essentially a group chat that you generally need to be invited to. Let's walk through one of these travesties. I was a member of a channel for a new product we were launching - call it NewProductChannel. In this channel we had all the various stakeholders (about 8 people) that were involved in the product launch. The idea of the channel was to make it simple and fast for engineering to talk to operations or risk to talk to finance. Sounds great in theory. What quickly happens is that while engineering and operations are chatting together, risk and finance are inundated with meaningless conversation. Yes, it can be good that risk and finance see those conversations so they can step in if it impacts their team or understand any potential delays. What happens instead is that they stop caring about the hundreds of irrelevant messages. Then, when finance wants to discuss a topic with risk, they have to scroll through hours/days of message to find where they last discussed an outstanding issue. This is madness. This type of project and work should generally be done asynchronously. A daily update e-mail with the product owner relaying to all teams all important updates and a project tracker/checklist in google docs so anyone can check at any time to see the status of each element. This way you have almost real-time updates on everything about the product launch minus the 2,000 messages on the minor details. And you control the cadence at which you get the messaging. You could argue that Slack should be used in conjunction with the daily e-mail update and the tracker. This is patently absurd. 75% of the messages were irrelevant to the people involved (should have been direct messages) and then, to make matters worse, there is an expectation that everyone has read the messages. The logical conclusion is you get a stakeholder, let's call her Katie, saying: "I told everyone in the NewProductChannel about the changes! If I can't communicate it there then what is the point of the channel?" Good question Katie - there is no fucking point to the channel. Slack anger level: High 2. It limits the depth and communication of ideas. If you are sending an internal e-mail to all stakeholders involved in a project, you generally:

Slack renders all of that obsolete. It turns mature, educated employees into teenagers communicating via whatsapp. Let's walk through an example. Assume you are building the customer flows/journey for your new product. You chatted with engineering in the morning and came to the conclusion you'd have to remove one of the on-boarding features to ensure you could still hit your ship date and simplify your MVP. Here is what that communications looks like on an e-mail: "Hi all: After discussing with Katie and John this morning, we believe that we should take Feature X out of the MVP of the product launch. Here was our thinking behind it:

When we launch we will be tracking to ensure that the expected customers remains consistent (sub 10%). I will be responsible for tracking and will report back post launch. If you have any questions please let the group know by close of play today." Here is what the same communication looks like in Slack "@channel I spoke with engineering this morning. Will need to get rid of feature X in this version of the build to hit ship date. Simplifies things. Let me know if you have any questions." So why did Slack suck for this?

These are scary differences for anyone in a fast moving business. Making matters worse, Slack finds more maddening ways to make everyone's life worse. For example, they added an ability to respond to a particular message with a separate thread. So now, you don't know if you can even scroll through the channel, you might have to scroll through the sub-threads. Fuck Slack. Slack anger level: Irate 3. Take e-mail anxiety and ratchet up slack anxiety by factor of 10. Its exhausting and anxiety-ridden enough to wake up or come back to 40 unread e-mails (I'm an inbox zero fan). Slack is massive multiplier to this exhaustion and anxiety. Instead of just 40 unread e-mails, I now have to add 20 slacks from 7 different people and a lot of buzz in some of the channels I'm in. Now this wouldn't be that bad if people treated Slack like e-mail. With an e-mail its generally accepted, at least in my experience, that a 24-hour turnaround for non-urgent e-mails is appropriate. And urgent e-mails are usually marked as such or you know you need to respond because you get to read the subject line and who it came from. Slack destroys the elegance of e-mail in three ways.

The nail in the coffin when your company uses both e-mail and Slack is you don't know where information is stored or communicated. If someone sent me a slide deck 2 weeks ago, now I have to check e-mail and slack to find it. So essentially we added the worst communication tool man has ever invented as the primary means of communicating in our organization. Yay. Slack anger level: Fiery hatred of a 1,000 burning suns. 4. Let's stop taking crazy pills and go back to e-mail. E-mail works really well if you know how to use it. Slack ruins lives. That's all you need to know. Slack anger level: None - full cathartic exercise complete. Also, thanks to John Biggs at TechCrunch for his hatred of LinkedIn for inspiring me to write this. "Super Nintendo, Sega Genesis

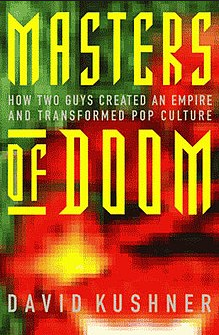

When I was dead broke, man I couldn’t picture this" Notorious BIG, Juicy David Kushner’s Masters of Doom: How Two Guys Created an Empire and Transformed Pop Culture was released in 2003 and reading it now was a blast from the past. The book chronicles John Romero and John Carmack, two brash young programming superstars who would create Wolfenstein 3D, Doom, and Quake. These were 3 of the most iconic games of all time (and a large part of my early childhood). The most fascinating part of the book was the scale of company the two John’s built. They created a gaming empire with essentially 5 programmers and a few business and administrative helpers. That’s it. 5 guys, gallons of diet cokes, and stacks of pizza boxes created a massive business in the mid-90s. This was one of the first “holy shit the internet can do incredible things moments.” The book is a quasi-business history, quasi-biography (of the two Johns), and quasi-cultural discussion of violent video games. I absolutely loved it. Here are my takeaways. "50 told me go head and switch the style up

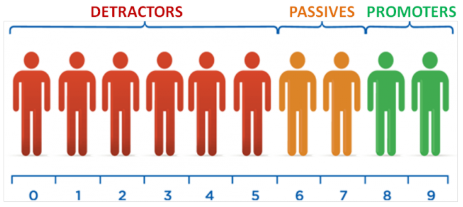

and if they hate, let 'em hate, watch the money pile up." Kanye West, Good Life About 3 years ago, the CEO of my company came over to me and said we should roll out NPS and asked me to lead the effort. I told him I had never heard of NPS. Probably not a great start. He gave me a brief overview of NPS - its promulgation by Bain & Company and the HBR article that unveiled NPS to the broader world (very good article to understand the correlation between company growth rates and NPS). I was then left to my own devices to figure out what to do next. "Chasing paper paper chasing, look that's all we know

Coming through the neighborhood on them 24's Bet a thousand, shoot a thousand, n**** up it some more Fast money, Cash Money, that's all I know" Birdman, Get Your Shine On I can't for the life of me remember how this book was recommended to me (my best guess is via the Acquired podcast), but it was a thrilling look at the DotCom bubble right before it burst with a passenger seat with the man who helped fuel it, Jim Clark. The book chronicles the tale of Jim Clark's rise in Silicon Valley and the start of the Dotcom era all the way to its peak (the book was published in 1999, 1 year before the bust). Starting with Jim Clark's Silicon Graphics to Netscape to Healtheon, it's a tale of how Silicon Valley became the hottest place to work and chase money, creating its own counterculture and breaking all the rules along the way. Overall impression: Fun read with great insight into the 90s Dotcom go-go era. Falls a little short for me in being a must read because we don't get the same passenger seat ride when the tech bubble burst and all these companies got their comeuppance. For fans of business eccentrics and learning more about the history of the Valley, its a really fun book (I like to think of it as beach reading for nerds). My takeaways and favorite excerpts: "Promise me you gon' stack, promise me you gon' ball /

Promise me you'll invest three fourths of it all" Andre 3000, Hollywood Divorce Elad Gill is an entrepreneur and investor who was at Google when it went from 1,500 to 15,000 employees and, when Twitter acquired his company, he saw Twitter grow from 100 to 1,500 employees and stayed on as an advisor to the CEO/COO as its growth continued. He's also invested in Coinbase, Airbnb, Square, Strip, and many others. He recently published the High Growth Handbook to help entrepreneurs survive their high growth phase. Here are my key takeaways. |